ABSTRACT :

FULL TEXT :

INTRODUCTION

For decades, Palestinian American prose, poetry and works of art have been approached through the perspective of exile and post-colonial studies. Whenever “Palestine” is mentioned in any work, notions like “diaspora,” “resistance” and “the right of return” are automatically used to scrutinize a text/artwork. Though they are intrinsically acknowledged, they also cannot be limited to examining the work itself. Hence, I contend, repeating the same patterns and techniques in analyzing Palestinian American works of art denies the artists their daily lived experiences, their present, their citizenship rights in the land they live in, work and produce the very artwork being explored.

This study aims to scrutinize notions of “exile,” and “homeland” through the selected works of art. Taking the very personal experiences of Naomi Shihab Nye and Manal Deeb as presented in their selected works as cases in point, the works will be tackled as examples of different kinds of border crossing which resist the culture of exclusion. The selected works and experiences will not be viewed through the East/West binary, but rather as a universal quest that can apply to different kinds of crossing intrinsic for mapping an authentic universal sense of self and homeland that can resist the reality of the colonized and exilic Palestinian condition.

The study explores and analyzes the selected works of both artists as examples of the art of those living between the borders of more than one culture, language, reality, etc., in search for an authentic sense of self and home in exile. The fluidity in shifting between the past and present, between two languages, and between the personal and the collective is also explored. The study also focuses on the personal documentation process of each artist, viewing their works as therapeutic acts towards coming home to the self.

WHERE IS HOME

“Love means you breathe in two countries.”- Nye1

Exile triggers images of the loss of home or forced detachment from an ancestral land that holds a national language, culture and religion. It is common to theorize and speak of people who are actually geographically exiled by force, as their experience might be filled with loss, dislocation and trauma. However, in thinking about exiles who have never witnessed the act of being exiled, but inherited the exilic status from their ancestors, or immigrants choosing to leave their birthplace and live in another, using the same notions to describe their experiences will not be appropriate. However, the ancestral “homeland” cannot be detached from their consciousness; it becomes an intrinsic part of their inherited experience.

The experience of exile as an “unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home” is explored by Edward Said in his Reflections on Exile.2 The oscillation between the tragic melancholic voice and the romantic view of home, on the one hand, and exile as a fact, or rather an inherited alternative empowering condition, on the other, is remarkable. As Said writes, “Exiles cross borders, break barriers of thought and experience.”3 Said argues that this state of being in exile creates a pluralistic vision. As he puts it: “Seeing ‘the entire world as a foreign land’ makes possible originality of vision. Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimension.”4

Janet Abu-Lughod discusses the state of “inherited exile,” in “Palestinians: Exiles at Home and Abroad” (1988). She argues that theories have been focusing on exile as a temporary or transitional state, failing to cover it as a permanently inherited condition. Palestinians in exile today may not have lived the experience of emigrating home; she argues, “Only a small proportion of Palestinians alive today, therefore, actually experienced the trauma.”5 Exile brings with it notions of homeland and return; however, referring to Abu-Lughod’s claim, how can the act of “return” be comprehended with the absence of traumatic dislocation? The meaning of return is raised by Edward Said in After the Last Sky (1986). As he puts it:

All of us speak of awdah, ‘return,’ but do we mean that literally, or do we mean ‘we must resort ourselves to ourselves’? The latter is the real point. . . Is there any place that fits us, together with our accumulated memories and experiences?” 6

In the same vein, in her essay “Visions of Home: Exile and Return in Palestinian-American Women’s Literature” (2004), Lisa Suhair Majaj suggests that as an exile, to return is “to come home to the self.”7 Majaj sheds light on the process of healing the rupture between the past and present, the home left in the past and the home lived in or born in the present through writing and documenting one’s experience. She argues that through the process of writing their own experiences, Palestinian artists in exile seek to understand their identities “as Palestinians, as Americans, as writers… exploring the possibilities of return. But ‘return,’ in their work, signals a return not just to Palestine or Palestinian history, but also new versions of home and selfhood.”8 Through writing and artistic self-expression, the borders between home and exile, the past and the present are crossed. The sense of home here becomes closely attached to the self and the personal experiences of the artists/writers.

As Said questions the nature of “return” in After the Last Sky (1986), Majaj has a similar concern for the nature of “return.” As she puts it, “What kinds of return are possible for Palestinian Americans, often geographically and generationally removed from the direct experience of exile, yet deeply affected by its realities?”9 Majaj argues that “If homecoming is a movement, a journey, homemaking is an act of creation. And as the history of literature makes clear, countless writers have responded to the pressures of exile by creating a home in writing.”10 Hence, the concept of the “right of return,” shifts to become “writing to return.” Thus, when official narratives fail to address personal experiences, writing and artistic documentation become a resort or a home to come to.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Born in Palestine, Palestinian American visual artist Manal Deeb (1968) moved to the United States at the age of 18. Through her artwork, Deeb tends to form a visual manifestation of her identity, defying rigid sense of time and space and combining both her ancestral Palestinian heritage and her present daily lived experience in the United States where she studied, still works and lives. Deeb uses collage surrealism technique in her paintings and digital work as a means to unite the past and present in one work. It is worth noting that the “past” that is mentioned here and used in Deeb and Nye’s work is not limited to the artists’ own past or memory but is extended to their previous generations and heritage that are part of forming who they are at the moment.

Deeb’s technique allows for constructing a space that combines both her backgrounds together, forming deeper metaphors of the self and the home. What is precisely interesting about Deeb’s work, is how she plays with and mixes different elements and techniques in her visual work, combining modern techniques of visual art with Arabic calligraphy and Quranic verses. This mixing and matching of elements can be viewed as a process of combining and affirming a multiplicity of experience.

Born in the United States, Naomi Shihab Nye (1952- ) is a Palestinian American poet and writer who is known as a “wandering poet.”11 Nye grew up between San Antonio, Texas and Jerusalem. Born to a Palestinian Muslim father and a European-American, Christian mother, Nye is one of the prominent contemporary Arab-American writers.12 Living within a bicultural context, Nye is conscious of her Palestinian American, western eastern,13 Christian and Muslim heritage and affirms it through her poetry where she rewrites her own story. In Nye’s poetry, the past and present are interwoven to honour the multiplicity of her identity.

Nye’s ethnicity as a Palestinian American writer forms the basis for connecting all other ethnicities. In Grape Leaves: A Century of Arab- American Poetry (1988), Nye observes that writers, in general, are builders of bridges. She adds that “bicultural writers who are actively conscious of or interested in heritage build another kind of bridge as well, this one between worlds. But it’s not like a bridge, really—it’s closer, like a pulse.”14 Hence, the presented analysis of Nye and Deeb’s work is based on this understanding, as their negotiation with their past/heritage is seen as a main aspect in connecting with the world.

ANALYSIS: MIXING AND MATCHING

In her poem “Different Ways to Pray” from her 2002 collection 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East , Nye demonstrates different practices in communicating with God. She represents the multiple ways of praying she observes around her. The poem is divided into seven stanzas; and in each one she describes those different practices, including the traditional Muslim prayer. In choosing seven stanzas, Nye might be referring to the ritual of the seven cycles the pilgrims perform around the Kaaba. However, the number seven is also a symbolic number in Christianity, Judaism and spiritual traditions.

Nye opens the poem saying, “There was the method of kneeling, / a fine method, if you lived in country / where stones were smooth.”15 In the first stanza, Nye refers to the prayers of Palestinian Muslim women kneeling and touching stones with their knees while praying. The “stones” become a historical and political symbol as they refer to the First Intifada, known as the Stones Intifada, where Palestinians used the stone as a symbol of non-violent resistance against Israeli aggression. Stones become a symbol intermingled with prayers, a sign of struggling against occupation and hoping for its end. Moreover, prayers are not depicted as a passive way of resistance that relies on God’s help; but they affirm that there are real physical and symbolic acts of resistance.

Nye refers to Islamic prayers that include reciting Quran where “small calcium words uttered in sequence, / as if this shedding of syllables could somehow / fuse them to the sky.” 16 The prayer is done downwardly touching the ground through reciting certain words, while in the second stanza shepherds are praying upwardly lifting their arms to the sky and speaking freely with God, asking for relief from pain:

Under the olive trees, they raised their arms

Hear us! We have pain on earth!

We have so much pain there is no place to store it!

But the olives bobbed peacefully

in fragrant buckets of vinegar and thyme.

At night the men ate heartily, flat bread and white cheese, and were happy in spite of the pain,

because there was also happiness. 17

Through the shift in voices between “they” and “us” in the first two lines, Nye crosses the border between binaries, dismantling the western us/them discourse, as both pronouns are used to draw upon the same people. The image of olives, white cheese, bread and eating are key images that are used frequently in Nye’s poetry, as well as the fusion of pain and pleasure as part of the human experience. There is a sense of solidarity and sharing met with God’s blessing symbolized by the olive tree. Despite the sense of despair and pain, the poem culminates in “happiness” as a signifier of hope needed for sustaining resistance.

In the following stanza, Nye refers to the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca where Muslim pilgrims wear white linen and “circle the holy places, / on foot, many times,” and “bend to kiss the earth,”18 which is a very well-known scene for Arabs, to kiss the ground upon arriving. Nye draws upon Mecca as a space that includes people coming from all over the world, collectively circling in a spiritual tradition. In choosing prayers as the theme of this poem, Nye crosses the borders between people through drawing upon the spiritual aspect that attracts humanity, thus transforming differences and cultural clashes to sameness.

In the fifth stanza, Nye refers to “certain cousins and grandmothers” who had their own daily pilgrimage or travel as she says, “the pilgrimage occurred daily, / lugging water from the spring / or balancing baskets of grapes.”19 She describes them as the ones who are always “present at births, / humming quietly to perspiring mothers,” and who make dresses for the children, “forgetting how easily children soil clothes.”20 They are community caregivers and their kindness is depicted by Nye as another kind of prayer and spiritual act. She goes on mentioning young adults who live in America and do not care about praying, and the older ones who pray for them to pray:

There were those who didn’t care about praying. The young ones. The ones who had been to America.

They told the old ones, you are wasting your time.

Time?—The old ones prayed for the young ones.

They prayed for Allah to mend their brains. 21

In a few lines, the meeting between the two cultures and two generations is made, showing the difference, yet with an ability to make a conversation concerning this difference. Nye ends the poem by “Fowzi,” “who did none of this”, an old man who “spoke with God as he spoke with goats, / and was famous for his laugh.”22

In this poem, Nye demonstrates all these different ways of communication with God she objectively observes in her Palestinian community in a celebratory tone without being with or against any way of them. In his paper “The Dialect of Borders and Multiculturalism,” Tawfik Youssef rightly argues that Nye is pro-multiculturalism, presenting all religion as equal in her work; while encouraging personal exploration in choosing one’s faith.23 Moreover, in her paper “Identity in Naomi Shihab Nye,” Wafaa Al Khadra points out that in demonstrating these different ways of prayers without siding with any, Nye “ [i]dentifies and empathizes perfectly with those Moslems who go to Mecca for Pilgrimage,” just as she identifies with those “who did not care about praying.”24

In “Grandfather’s Heaven” from her 1995 collection Words under the Words: Selected Poems, Nye also refers to her western Christian family, where she says “Grandma liked me even though my daddy was a Moslem.”25 She starts the poem by, “My grandfather told me I had a choice. / Up or down, he said. Up or down. / He never mentioned east or west.”26 While she ends it by quoting her grandfather’s advice to her: “I hear you’re studying religion,” he said. / “That’s how people get confused. / Keep it simple. Down or up.”27 Although “Up or down” might have endless meanings to interpret in such context, however, her grandfather’s “simple” answer to Heaven was not satisfactory to her. It is an answer that has the binary of “either or” as if she resorts to studying religion and witnessing “different ways to pray,” going the hard way for a true, satisfying answer.

In many of her poems, Nye is keen on showing this stance of merging between oppositions and not resorting to one part of her identity in favour of the other. A fine example is her poem “Half and Half” from the collection Fuel: Poems by Naomi Shihab Nye (1998) where she opens it by:

You can’t be, says a Palestinian Christian

on the first feast day after Ramadan.

So, half-and-half and half-and-half.

He sells glass. He knows about broken bits, chips. If you love Jesus you can’t love anyone else. Says he. 28

Here, Nye is advised to stay in the safe side and embrace only one clear part of her identity, as it would lead her to being fragmented, or to be cut split in “broken bits” causing wounds. Nye refers to her father who chooses to pray “in no language but his own.”29 She ends the poem with:

A woman opens a window—here and her and here—

placing a vase of blue flowers on an orange cloth. I follow her.

She is making a soup from what she had left

in the bowl, the shriveled garlic and bent bean. She is leaving nothing out. 30

Like her father who chooses his own path, Nye refuses to stay in the safe path and follows those “windows” opening many directions and horizons, claiming space in all parts of her pluralistic experiences. She chooses to follow a mixture of colors, symbolizing various possibilities, and makes use of all her ingredients, “leaving nothing out”. Nye refers to food a lot, using the image of a dish that needs more than one ingredient to be cooked, referring to the makeup of her own identity.

Including religious allusions as part of cultural identity formation and fusion of opposites are also main themes in Manal Deeb’s artwork, whether through combining mixed materials or through providing opposite meanings in one work. Her mixed media artwork “This Camp is my Laughter,” (fig.1) is a work combining calligraphy, painting and a part of a tree branch, where both hope and pain are seen combined together. On a white background, a combination of materials is presented. At the upper- middle to the right is an incomplete painting of bars, only occupying a small part of the work. Behind those bars are some unclear figures, which may signify life away from the homeland in the refugee camp.

FIGURE 1. Deeb, Manal. This Camp is My Laughter. 2012, Mixed Media. ArtSlant. bit.ly/2UIuZVL.

There are also fragments of a human face, as a clear eye and mouth are seen, which signify a witnessing eye gazing at the oppressive reality and a narrative voice recording all uncertainties and pain. Storytelling, or in this context documentation, is one of the main tools used by both artists as a means of resistance. As Gloria Anzaldua puts it in This Bridge Called My Back , “I write to record what others erase when I speak, to rewrite the stories others have miswritten about me, about you.”31 What occupies the greatest space in this artwork are the tree branch and the Qur’anic verse :

إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ عَلَىٰ كُلِّ شَىْءٍۢ قَدِيرٌۭ

which translates in English: “for Allah Hath power over all things.”32 The tree branch is centrally located and glued on the painting in a vertical way, starting from its bottom, as if it is what is holding the whole composition.

Trees and plants are recurring elements in Palestinian American art and literature. In her poetry, Nye similarly uses images like fig trees, olive trees, almond trees and others. Trees, plants, fruits, and respectively food in this context give the sense of rootedness and bond with the earth and the homeland. In this regard, in an online published article by the Institute for Middle East Understanding (IMEU) Deeb touches upon her use of trees in her work:

My grandmother’s house is all gone, but in my mind, it’s still there. I remember playing by the fig trees as a kid, and I even have a series called ‘Memories of Trees.’ I often incorporate tree bark into my artwork to symbolize the Palestinian struggle. 33

The Quranic verse, taking the bigger space in the artwork, is what gives this sense of hope that God is capable of everything and that through faith those refugees in the camp can live with hope. Deeb intentionally changes the order of words in the Qur’anic verse, putting ٱللَّهَ / Allah “God” on top of the whole composition although the word comes second in the verse. By putting God’s name on top, in a position looking like a minaret, Deeb emphasizes her Islamic belief in God, witnessing all that is happening, and believing that God has power over everything, putting her hopes in what she strongly believes in. The title given to the artwork “This Camp is my Laughter” also refers to this hope, as laughter and hope that generate an optimistic resistant stance are found even in pain. Like Nye, Deeb is aware of the religious diversity in her Palestinian community, and demonstrates how it has a significant impact on forming her cultural identity and on giving hope to exiles.

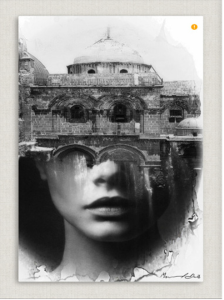

In her following digital artwork “Church of the Resurrection” (Fig.2), another religious icon is depicted where an image of Jerusalem’s iconic church is mingled with a portrait of a woman. The notion of resurrection holds in itself a deep belief and a promise of return or reviving, as if that usurped home is the source of birth and the only place for return. The two inserted photographs in figure 2 have the same equal size where half of the woman’s portrait appears with the church occupying the upper part of her face on her eyes and head, substituting and signifying her consciousness. In the original place of the eyes, the two windows of the church appear, as if the way she looks at things is coming from her place of origin. Although she is physically detached, those windows are her eyes, recording and seeing the unjust reality the Palestinians face in their homeland. The painting thus alludes to the fact that although the Palestinian land is geographically colonized, her mental space is metaphorically decolonized.

FIGURE 2. Deeb, Manal. Church of the Resurrection. 2018, Digital Work. YGalleri. www.ygalleri.com/

Unlike Deeb who as an eye witness depicts her Palestinian homeland from her own memory, Nye uses her post-memory instilled into her by her family to portray Palestine. Nye’s reflections on exile and Palestine as a homeland is quite often presented through the stories of her father or grandmother.

In Grape Leaves: A Century of Arab-American Poetry (1988), Nye speaks about having this multiple sense of self, asserting that: “Being bicultural has always been important to me: even as a child I knew there was more than one way to dress, to eat, to speak, or to think. I felt lucky to have this dual perspective inherent in my parentage, and I was encouraged to explore other ethnic and cultural perspectives as well.” 34

Nye’s tone that celebrates her reality in her poetry by embracing her bicultural identity allows for wider spaces and imagination for the self and home. Similarly, Deeb who presents the Palestinian elements and symbols through western media allows for a fluidity of integration between two cultures and two times.

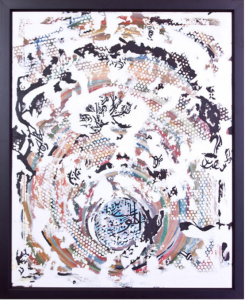

In her painting “Delirious in Exile” (fig.3), Deeb demonstrates another example for such a quest; however, Deeb’s portrayal of her identity and her position in the world is different from that represented by Nye. By choosing this title for the painting, Deeb chooses her position of being in exile, referring herself to her Palestinian homeland. The word “delirious” ambivalently combines both notions of confusion and ecstasy. The painting’s base is white with patches of paint done in a cyclic way, giving the work a feeling of motion and continuity. The use of the white colour as a foreground and peeling it to show the paint underneath is one of Deeb’s painting characteristics. The work has a mixture of paint colours, with patches of white as a foreground and background for the work. Using it as a base suggests the ability to paint and create the self from start.

FIGURE 3. Deeb, Manal. Delirious in Exile . 2012, Mixed Media. ArtSlant. bit.ly/2UIuZVL.

Through showing what is hidden beneath the multiple layers of her work, the notion that there are always multiple realities found in digging deeper is achieved. Although the deeper layer is painted in a fluid continuous motion, the white patches in the upper layer cut its fluidity, giving the work a feeling of ambiguity and uncertainty along with the connectivity and continuity of the portrayed cyclic motion. The whirlpool holds fragments of Arabic letters, and a tree as a symbol of home, reflecting blurred memory.

The centre of the whirlpool is blue and has Arabic letters. According to Jill Morton, a colour psychologist, blue as a colour has references in nature and psychological symbolism. As blue stands for oceans and rivers, sources of life, it is psychologically connected with spirituality, truth and tranquility.35 Despite this colourful wide and diverse state of whirling, choosing blue as the centre of the composition, accompanied by the Arabic letters, Deeb connects water as the centre of life with her Palestinian identity as her harbour. At the centre appears the Arabic word هُوَ/ Hu, referring to God that is usually recited in Sufi zikr/hadra,36 which is a collective spiritual ritual. The whole painting seems to create the feeling of a whirlpool that absorbs different things that move in a harmonious cyclic way with one solid centre.

The depicted whirling state gives the effect of a spiritual prayer that is linked to the spiritual Sufi tradition. Whirling is a high spiritual act that connects a person with the whole universe and the Divine; it is a channel that crosses the borders between the materialistic world and the metaphysical one, connecting the earth with the sky, and the past with the present in an eternal cyclic movement. The small white circles depicted on the whole painting can be seen as a bee nest, symbolizing both life and home creation, as bees are known for continuously creating their own nests/homes themselves.

Both Deeb and Nye reflect a presentation of identities being in continuous motion, while accepting and absorbing their multiple layers formed by travelling and moving between different worlds, surpassing borders. Building on this, the two artists choose to write, paint, document and create their own identities through literature or art.

Nye takes writing as a tool, not only for documenting her path, but also for sewing the different parts of her identity together, reaching “The Whole Self,” through poetry, where she can find a home for herself. Through writing, she crosses the borders between those diverse parts and also communicates with people of her two or more different cultures. On her relationship with her Palestinian family, Nye notes that since she was writing as a child she felt that she “was recording things for them or communicating with them” through writing. She felt that she “was bridging something” as writing helped her “identify what makes the whole geography of our lives.”37 In “From One Friend to Another,” Nye asserts that: “Literature is one of the best bridges among us. And it is a beautiful bridge without a toll. Books, stories, poems, encouraging a deepened empathy and respect for one another, especially for those ‘others’ whom one might have imagined to be ‘unlike ourselves,’ serve a great purpose in the current sorrowing time.” 38

In the same vein writes Majaj on Palestinian American writers including Nye, who have the ability to create “a home within” through writing. Majaj calls Nye “a traveler in the world able to make a home where she goes.”39 Majaj asserts that: “The writer who negotiates exile, of whatever sort, is seeking not just a return to a particular geographical or emotional space, but is seeking to recreate the self in relationship to the world. If homecoming is a movement, a journey, homemaking is an act of creation. And as the history of literature makes clear, countless writers have responded to the pressures of exile by creating a ‘home in writing.’”40

CONCLUSION

“Humanism is the only—I Would go so far as saying the final—resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure human history.”

― Edward W. Said41

Through their work, both Nye and Deeb pave a path towards reaching a sense of home. However, it is not a linear one, as through their journey they negotiate their own experiences, shift, shape and reshape its mean- ing. Along the same line is their identity negotiation as their identities are formed and reformed through exploring and crossing the borders of the past and the present. When a classical fixed notion of home becomes in- adequate, the meaning of home extends geographic borders, encompassing both dislocation and relocation in its making. Exile becomes a central experience closely connected to the meaning and making of home. The meaning of home in such a context becomes actively shaped and reshaped, as well as the identity is seen under continuous construction. Although the path is personal, it is never individual, as both artists create their work to communicate with others. Through sharing their writing or artwork, they both go from their very deep emotions and experiences into a larg- er connective and collective consciousness. Both Deeb and Nye have the urge to speak, document and create while continuously crossing different borders.

Through freely moving between the present and the past crossing the borders between generations, time and space, both artists reclaim them- selves. By redeeming their own pain, they transform it into something valuable, followed by an urge to share with others so they too may be em- powered. Through constantly seeking the act of creation for healing and communicating, writing and rewriting, along with claiming loss and hope, artists and their stories are transformed from a state of passivity into agency. Moreover, the act of writing/artistic creation is not only seen as an active process claiming the right to discover and build the identity, but it also becomes a call for social change, as in its core it dismantles officially organized narratives of viewing reality.

“Home is not a place because it extends from the innermost self throughout the world…

we create it anew every day by actively and lovingly going about our daily lives” –

Jutta Ittner 42

NOTES AND REFERENCES :

- Nye, Naomi Shihab. “Two Countries” In 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East, Greenwillow Books, 2002.

- Said, Edward W. “Reflections on Exile.” In Reflections on Exile: And Other Essays, 137-148. Granta, 2001.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. “Palestinians: Exiles at Home and Abroad.” Current Sociology, vol. 36, no. 2 (1988): 63. doi:10.1177/001139288036002007.

- Said, Edward W., and Jean Mohr. After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives, 33. Pantheon Books, 1986.

- Majaj, Lisa Suhair. “Visions of Home: Exile and Return in Palestinian-American Women’s Literature.” Thaqafat, (2003): 7–10.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “No Human Is Illegal.” The Clemente Program in the Humanities, (2017). clementeworcester.com/event/nohuman

- Majaj, Lisa Suhair. “Arab-American Ethnicity: Locations, Coalitions, and Cultural Negotiations.” In Arabs in America: Building a New Future, edited by Michael W. Suleiman, Temple University Press, 1999.

- Since this study dismantles the East/West binary, I choose to use both words in lower case letters aiming at finding new understandings to the notions they hold.

- Orfalea, Gregory, and Sharif Elmusa, editors. Grape Leaves: A Century of Arab American Poetry, 38. Interlink Books, 1988.

- Nye, Naomi Shihab. “Different Ways to Pray.” In 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East, 3-5. Greenwillow Books, 2002.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Youssef, Tawfik. “The Dialect of Borders and Multiculturalism.” Sino-US English Teaching, vol. 12, no. 1 (2015): 57. doi:10.17265/1539-8072/2015.01.007.

- Alkhadra, Wafa A. “Identity in Naomi Shihab Nye: The Dynamics of Biculturalism.” Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences, vol. 40, no. 1 (2013): 190. doi:10.12816/0000628.

- Nye, Naomi Shihab. “Grand Father’s Heaven.” In Words under the Words: Selected Poems, Far Corner Books, 1995.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Nye, Naomi Shihab. “Half and Half.” In Fuel: Poems by Naomi Shihab Nye, 60. BOA Ed, 1998.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Moraga Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldua, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, 167. SUNY, 2015.

- Ali, Abdullah Yusuf. The Meaning of the Holy Qur’an: Text, Translation and Commentary. Mumbai: Darul Quran, 2006.

- Elmusa, Karmah. “Manal Deeb: Artist.” Palestinian-American Profiles (2014) imeu.org/ article/manal-deeb-artist.

- Orfalea, Gregory, and Sharif Elmusa, editors. Grape Leaves: A Century of Arab American Poetry, 226. Interlink Books, 1988.

- Morton, Jill. A Guide to Color Symbolism. COLORCOM, 1997.

- Zikr means remembrance, and Hadra means presence. Zikr or Hadra are collective gatherings, where sufi disciples meet together to recite names of God and Quranic verses, chant sufi poems, and move collectively in circles. Through this spiritual gatherings, Sufis seek the connection between the material world and the divine realm.

- Majaj, Lisa Suhair, and Naomi Shihab Nye. “Talking With Poet Naomi Shihab-Nye.” Al Jadid, vol. 2, no. 13 (1996). aljadid.com/content/talking-poet-naomi-shihab-nye.

- Nye, Naomi Shihab. “From One Friend to Another.” English Journal, vol. 94, no. 3, (2005): doi:10.2307/30046415.

- Majaj, Lisa Suhair. “Visions of Home: Exile and Return in Palestinian-American Women’s Literature.” Thaqafat (2003): 10-12.

- Ibid.

- Said, Edward W. “Orientalism 25 Years Later” (2003).

- Ittner, Juta. “My Self, My Body, My World.” In Homemaking: Women Writers and the Politics and Poetics of Home, 66. Routledge, 1996