‘Moses in Judaism, Christianity and Islam’

In September 2017, a conference under the title “Prophet Moses in Judaism, Christianity and Islam” was held at the Moses Memorial in Mount Nebo/Madaba-Jordan (Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land) to commemorate 800 years of Franciscan presence in the Holy Land. The conference aimed at sending a message of peace, mutual understanding and respect of difference with the belief that genuine interfaith dialogue and trialogue has to be preceded by religious tolerance that acknowledges differences and celebrates our distinctive paths. The life of Prophet Moses is an example that can unite and facilitate dialogue between the followers of the Abrahamic religions.

The conference was organised by the Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies (RIIFS) and the “Giovanni XXIII” Foundation for Religious Sciences of Bologna, in conjunction with the Italian Embassy in Amman and with support from the Delegation of the European Union to Jordan, under the patronage of HRH Prince El Hassan bin Talal and HE Mr. Ján Figel (former EU Special Envoy for the Promotion of Freedom of Religion or Belief).

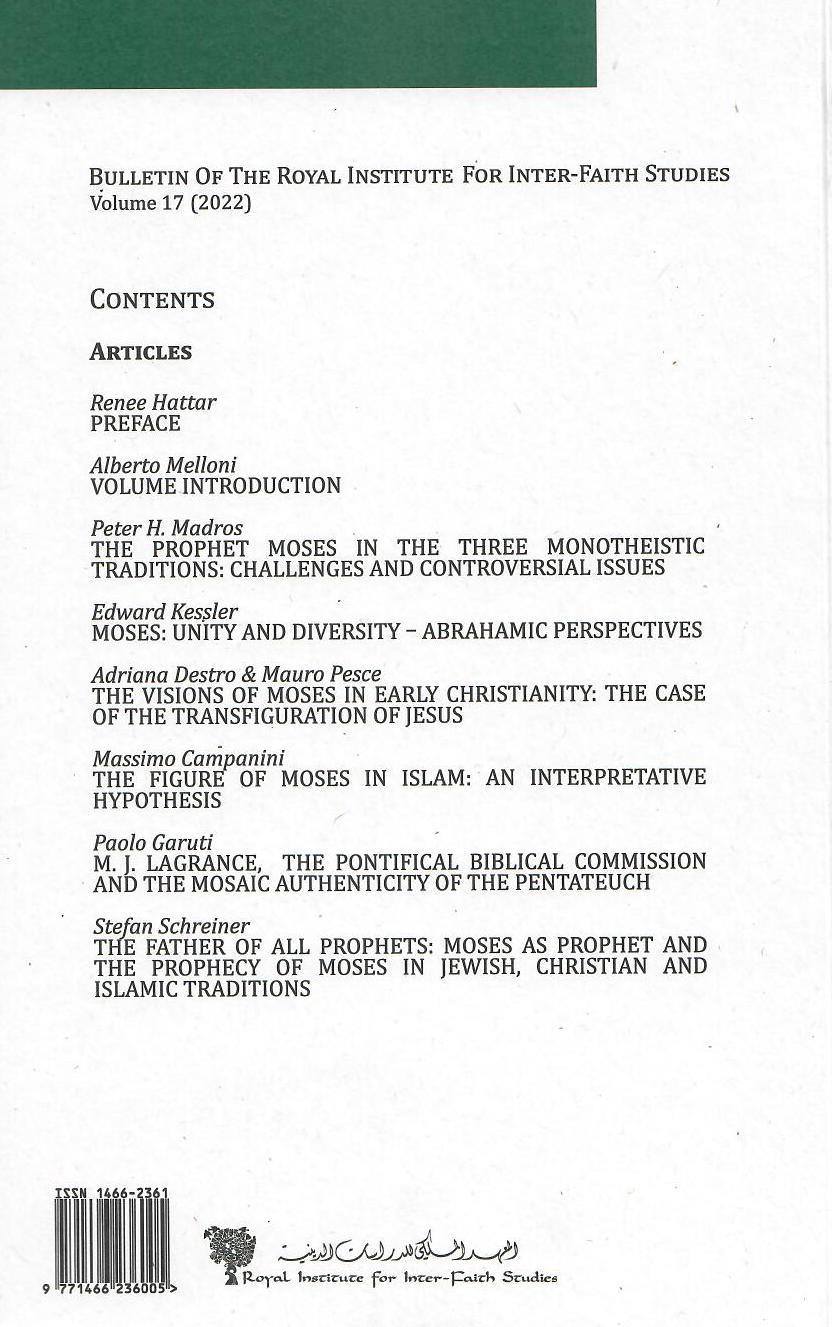

The current volume of the Bulletin of the Royal Institute of Interfaith Studies (BRIIFS) contains the contributions of special scholars from different countries who gathered at Mount Nebo and discussed Moses in the sacred texts and in the three religious traditions.

MOSES MEMORIAL IN MOUNT NEBO (FRANCISCAN CUSTODY OF THE HOLY LAND)

34:1 Then, Moses climbed Mount Nebo, from the plains of Moab to the top of Pisgah across from Jericho. There the Lord showed him the whole land-from Gilead to Dan,

34:2 all Naphtali, the territory of Ephraim and Manasseh, all the land of Judah as far as the Mediterranean Sea,

34:3 the Negeb, and the whole region from the Valley of Jericho, the City of Palms, as far as Zoar.

34:4 Then the Lord said to him, ‘This is the land I promised on oath to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, when I said: ‘I will give it to your descendants’. I have let you see it with your eyes, but you will not cross over into it.’

34:5 And Moses the servant of Lors died there in Moab, as the Lord had said. (Deuteronomy 34)

Mount Nebo is situated in the northwest of Madaba, Jordan. Mount Pisgah, of which the Bible speaks (Ras Siyagha), extends toward the west but is lower in altitude (710 meters). Toward the south, the Khirbat al- Mukhayyat slope (790 meters), used to be the location of the city of Nebo.

The Custody of the Holy Land is a religious Order in the Catholic Church which belongs to the Order of Friars Minor, the Franciscans, who arrived in the Holy Land in 1217 with St Francis, their founder. According to the Order, Holy Places are not just stones; they are “the manifestation, the footprints of the passage of God in this world and the echo of the words of the Lord who spoke to us through prophets and apostles.” (1)

FATHER MICHELE PICCIRILLO, FRANCISCAN PRIEST AND ARCHAEOLOGIST

The Order’s interest and mission to Holy Sites included their important archaeological work in Madaba. A protagonist of the Order in this field was Father Michele Piccirillo, a Franciscan friar, historian and archaeologist. His journey in Jordan began in 1972 when he was entrusted with the restoration of the mosaics of the Church of Saints Lot and Procopius at Khirbet el-Mukhayyet in Madaba. (2)

Father Michele was very devoted to his work on the site, and his name since then was connected to Mount Nebo. He had collaborators gathering around him from all over the world including students, archaeologists, conservators, restorers and researchers who were devoted to his views and work. His work had led to the discovery of important mosaics and inscriptions that led to the re-understanding of history. As “he brought to light the mosaic in the diakonicon at the Memorial of Moses in Nebo. He completed the excavation of the Church of the Virgin at Madaba with the complete reading of the dedicatory inscription. He identified the city of Um er-Rasas – Kastron Mefaa, which is mentioned in several passages of the Old Testament.” (3)

He was not only keen on discovering through excavations but as well advocated for the necessity of preservation. Along with collaborating with individuals, he worked with local institutions such as the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. He cofounded the Madaba Mosaic School, which later became the Madaba Institute for Mosaic Art and Restoration. His work and contributions extended the area of Mount Nebo and Jordan,

As a professor in the Faculty of Biblical Science and Archeology in the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum of Jerusalem, he transferred his knowledge and experience to numerous students. With great sincerity, he promoted the archaeological heritage of Jordan. As a true scholar, he was fascinating in his accounts of art, archaeology and history. One of his most prominent publications is ‘The Mosaics of Jordan,’ published in 1993, which presents a rich variety of mosaic remains of the Byzantine and early Islamic periods in the country. (4)

PILGRIMAGE ROUTES AND VISITS OF CATHOLIC POPES

The pilgrimage to Mount Nebo is part of the broader pilgrimage experience that includes other religious sites in Jordan and the Holy Land. The route to Mount Nebo is sometimes connected to pilgrimage roads that link various biblical and historical sites.

Mount Nebo is often part of a larger itinerary that may include other destinations such as Bethlehem, Nazareth, and the Jordan River, among others. Mount Nebo is often included in these routes due to its association with Moses and the biblical narrative. For Christian pilgrims, the pilgrimage to Mount Nebo holds spiritual importance as it is linked to the life of Moses and his biblical story. The Memorial Church of Moses on Mount Nebo becomes a focal point for prayer and reflection. The act of following pilgrimage roads, including the visit to Mount Nebo, symbolizes a spiritual journey and commitment. Pilgrims engage in rituals, prayers, and reflections that enhance their connection to the religious heritage of the region.

Different Catholic Popes visited Mont Nebo. The First was Paul VI who arrived in January 1964, while the Church celebrated the Second Vatican Council. Followed by John Paul II’s visit in March 2000, celebrating a Jubilee Pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In his sermon at Moun Nebo, John Paul II said: “I have come to the heights of Mount Nebo, where Moses, before his death, looked out across the promised land, without being able to cross into it,” ”in sight of the city of Jericho, our gaze directed toward Jerusalem, let us lift up our prayer to almighty god for all the people in the promised land, Jews, Muslims and Christians.”(5)

Nine years later, His Holiness Benedict XVI arrived in The Holy Land in May 2009. His sermon, drew attention to the spiritual importance of Mount Nebo and its connection to the Jordan River as follows:

It is appropriate that my pilgrimage should begin on this mountain, where Moses contemplated the Promised Land from afar. The magnificent prospect which opens up from the esplanade of this shrine invites us to ponder how that prophetic vision mysteriously embraced the great plan of salvation which God had prepared for his People. For it was in the valley of the Jordan which stretches out below us that, in the fullness of time, John the Baptist would come to prepare the way of the Lord. It was in the waters of the River Jordan that Jesus, after his baptism by John, would be revealed as the beloved Son of the Father and anointed by the Holy Spirit, would inaugurate his public ministry. And it was from the Jordan that the Gospel would first go forth in Christ’s own preaching and miracles, and then, after his resurrection and the descent of the Spirit at Pentecost, be brought by his disciples to the very ends of the earth. (6)

His Holiness Pope Francis visited the Holy Land in May 2014. His pilgrimage was to commemorate the historical meeting between Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras I, which occurred 50 years ago.

MOUNT NEBO AND INTERFAITH DIALOGUE

More than eight hundred years ago, Saint Francis met Sultan Al Kamil in Damietta. After an attempt to convert each other, the two decided to remain friends, moving from conversion to conversation. Today we must reaffirm the important contribution given by cultural and religious heritage to the promotionofpeacefulandinclusivesocieties.Findingculturalaffinitieswhen having long-distance relationships, to improve understanding between and within faiths is an important task today. The ancient belief is that closeness to God can be achieved through the search for truth and compassion. (7)

According to Father Michele the scientific study of archeology was a vehicle of faith. As mentioned earlier, Father Michele was not only interested in unveiling the past through his work, his eyes were also on the future through highlighting the importance of preservation for future generations, adding to that, he was also interested in the present; in being present with his surroundings and the community he was working in. His experience did not have a colonial nature isolated from the community surrounding him, on the contrary he saw the importance of creating connections with locals. As he understood the importance of dialogue and valued friendships among his students and with the community he was working with. Throughout his stay he “introduced workshops for young people, professional courses for the restoration of the mosaic (in Madaba and Jericho) and guided visits for schools. In this sense, archeology was for Father Piccirillo a way to build peace.”8 In one of his latest diaries he writes:

Among the ways to contribute to understanding and peace among the peoples of the Middle East, on Mount Nebo we have chosen the one that is most congenial with our work as archaeologists (…). The restoration of the mosaics, mostly floors of the churches built in the region from the 5th to the 8th century, has given us the opportunity to preserve a heritage of art and faith and to develop at the same time a work of dialogue and friendship that are the foundations of peace. 9

If we consider the story of Moses in the three Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam, we can find many shared values and teachings of the sacred texts rich in spiritual symbols. This makes Mount Nebo a place of encounter among followers of all religions, a point which that the authors of this volume of BRIIFS clearly explored in their papers.

INTRODUCING THE ARTICLES

In his article on “The Figure of Moses in Islam: An Interpretative Hypothesis”, Prof Massimo Campanini offers us an analysis of the figure of Moses in the Islamic tradition, intricately woven into the Qur’an. It reveals a complexity that serves didactic and exemplary purposes. Positioned as the most cited prophetic figure, Moses parallels prophet Muhammad’s experiences and exemplifies a unique relationship with God.

“Moses in the Torah” by Dr Kamal Abdul Salam Hassan, explores the figure of Moses as a central one in Jewish history, emphasising his role as the greatest of all prophets who received the Torah on Mt. Sinai. It argues for the historical existence of Moses, citing the opinions of historians and referencing Breasted’s assertion that Moses is an Egyptian name. The paper aims to investigate Moses’ life and mission, focusing on the account in the Hebrew Bible, particularly the Pentateuch.

With a paper entitled “The Visions of Moses in Early Christianity: The Case of the Transfiguration of Jesus”, Adriana Destro and Mauro Pesce provide us with a text that delves into the multifaceted role of Moses in Roman- Hellenistic Judaism, with a specific focus on his visionary experiences as detailed in the Book of Exodus. It meticulously analyses the parallels between Moses’ visions and the transfiguration of Jesus in the Gospels of Mark and Luke, emphasising visual elements, temporal collocation, and the legitimising role of witnesses. Ultimately, the text underscores the pivotal role of Moses’ extraordinary visions as a framework for understanding and validating the experiences of Jesus in the Gospels.

‘Moses: Unity and Diversity from the Abrahamic Perspectives’ by Ed Kessler explores the dynamics of Abrahamic dialogue, particularly emphasising the shared figure of Moses among Jews, Christians, and Muslims. The exploration of common ground, such as shared scriptures and hermeneutical principles, is coupled with an acknowledgment of differences, particularly in the divergent interpretations of Moses in the New Testament and responses within each tradition. The text advocates for a nuanced approach in interfaith dialogue, striking a balance between identifying commonalities and managing differences with respect and understanding.

These perspectives culminate in two papers; the first by Fr Peter Madros entitled “The Prophet Moses in Three Monotheistic Religions: Challenges and Controversial Issues”, where the author suggests Moses as a potential bridge among adherents of the three monotheistic religions expressed through a prayerful sentiment. The Article critically examines the historical existence of Moses, considering perspectives from Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza to modern scholars. It explores alternative interpretations of Moses’ identity based on historical sources and argues for the indications supporting his historicity while asserting that Jesus Christ fulfils the prophecy according to Christian beliefs, while briefly touching on Islamic viewpoints.

The second by Stefan Schreiner entitled “The Father of All Prophets: Moses as Prophet and the Prophecy of Moses in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Traditions” in which the author explores the enduring legacy and multifaceted portrayal of Moses in the Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions’ perspectives. The article delves into Moses’ roles as a prophet and teacher, emphasising his unique immediacy of communication with God, which sets him apart from other biblical prophets. His prophetic tasks, including leading the Israelites out of slavery, are discussed, highlighting the divine nature of these actions. The article also explores Christian perspectives, where Moses is primarily seen as a lawgiver. In Islam, Moses is recognised as a significant prophet, with the Qur’an affirming his direct communication with God.

Finally, Fr Paolo Garutiexplores in hispaper “M.J. La Grange, The Pontifical Biblical Commission and the Mosaic Authenticity of the Pentateuch” the theological and historical shifts in understanding the authorship of the Pentateuch, particularly the views of Marie-Joseph Lagrange. Lagrange’s reconsideration of Mosaic authenticity was influenced by his trip to Sinai in 1893, where he confronted geographical and historical incongruities in the biblical narrative. This historical narrative unveils a nuanced debate within the Catholic Church at the turn of the 20th century, reflecting a delicate balance between biblical scholarship, theological considerations, and the challenges posed by evolving perspectives on biblical authorship.

At the end of the conference, its participants launched a “Message from Mount Nebo” where they expressed their wish for this work to be continued on other occasions between scholars and representatives of the three religions, in the “spirit of Mount Nebo.”

END NOTES

- Webit.It. “The Custody and Its History.” Custodia Terrae Sanctae, n.d. https://www.custodia. org/en/custody-and-its-history.

- Officer, Development. “Remembering Father Michele Piccirillo.” Acor Jordan, October 8, 2018. https://acorjordan.org/2018/10/07/remembering-father-michele-piccirillo/

- Ibid. (see Jos 13.18, 21.37, Jer 31.21, 48.21)

- Khatib, Maha. The Minister of Tourism and Antiquities. “IN MEMORIAM FATHER MICHELE PICCIRILLO – A TRIBUTE .” DoA Publication Archive, November 12, 2008.

- D. Politis, Konstantinos. “Father Michele Piccirillo 1944–2008.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 2009. DOI: 10.1179/174313009×437792 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1179/174313009×437792.

- Webit.It. “The Custody and Its History.” Custodia Terrae Sanctae, n.d. https://www.custodia. org/en/custody-and-its-history.

- “Pilgrimage to the Holy Land: Visit to the Ancient Basilica of the Memorial of Moses at Mount Nebo (May 9, 2009) | BENEDICT XVI,” May 9, 2009. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2009/may/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20090509_memoriale- mose.html

- Talal, El Hassan Bin. “Da Conversione a Conversazione Tra Le Religioni.” Avvenire, October 15, 2019. https://www.avvenire.it/opinioni/pagine/da-conversione-a-conversazione-il-ruolo-di-guida-delle-religioni

- ArcheoMe, Redazione. “EMINENT FIGURES | Father Michele Piccirillo, the Friar Who Built Peace with Stones and Mosaics.” ArcheoMe, October 27, 2020. https://archeome.it/eminent- figures-father-michele-piccirillo-the-friar-who-built-peace-with-stones-and-mosaics/

There is a paradigm that has stabilized around what is commonly called “interreligious dialogue.” It prepares and expresses an intention of dialogue by distinguishing between use and abuse of religions: it attributes all violence to the abuse, claims all the ability to neutralize conflicts for the moral principles that would constitute the appropriate use of faiths, and ultimately offers a selected number of “religious leaders” the opportunity to explain the destiny of fraternity among communities and put an end to a history of tension and cruelty – not only among themselves, but also within themselves – that not infrequently seeps into the present.(1)

This is a paradigm that has shown its effectiveness when it has reduced the recruitment ability of groups and currents (sometimes referred to as extremist, terrorist, or “radical,” with a quite significant resemantization of this word), which founded in a hermeneutic manipulation of the sacred text the use of war, terrorism, and violence as a duty of the true believer. But it is a paradigm that also soon showed its limits when it proved itself incapable of eradicating the seduction of violence and the thirst for blood that is always able to find motivations, footholds, and pretexts within religious universes.

There is a different way, apparently not more effective, but in the long run more profound. It starts, instead, from the consideration that every spiritual experience can be the basis for violence or compassion, contempt for the other or social friendship. It is based on the grounds of the responsibility that every religion – if and when it constitutes a free assumption of a higher dutifulness – assigns to those who make that gesture of freedom and consciousness of oneself and of the other. This way starts from the assumption that there are no “religions” in the abstract: but only religious traditions grafted into cultures, and that peace between cultures is essential to understanding between faiths, being much more than a dialogue in which one can curb belligerent instincts but not necessarily devitalize them. And that therefore the richness of the hermeneutics of each sacred text, the plurality of interpretations, constitute that “one” path in which each walks with the weight of one’s own history from a time of violence to a time of cohabitation, from the altar of fratricide to the city that bears the name of the son.

Belonging to this second strand is the attempt made on the hills of Madaba thanks to the welcome of the Royal Institute for Interfaith Studies, of the Franciscans friars who, after Fr. Michele Piccirillo’s excavations, completed the restoration of the Basilica of Moses, and of the Foundation of which I have the honor of being a part. Central to the aforementioned attempt in Madaba, was the figure of Moses.

Maestro of Israel, Christian saint, prophet of Islam, the life of Moses –liberator, legislator, and guide– is marked by the incompleteness of his path, which stops at the sights of the promised land, and which for this reason provokes a whole interpretation that interpolates biblical and Qur’anic dictate, to restore a meaning –or rather, many meanings– to an event that seems to demand one to be integrated into it.

Specialists in Jewish, Islamic, and Christian exegesis have measured themselves against this figure by retracing interpretive efforts: what emerged was a restlessness of the theologies, which extends even outside the theological debate. Indeed, it is well known that Sigmund Freud, in 1939, that is, at the end of his life, dedicated three essays to Moses, which compose a work that is both enigmatic and testamentary. David Meghnaghi, one of the most consistent readers of the work, in fact explains that the entire argument of the three essays could do without the starting postulates that Moses was an Egyptian prince, later assassinated. Freud surreptitiously suggests that he basically did not need them in the folds of an ambiguity-laden writing, whose cross-references and recapitulations create suspicion and doubt rather than thinning them out. As Freud teaches, the tortuousness of argumentation reflects “the presence of insufficiently resolved thought that complicates things,” or “the stifled voice of self-criticism on the part of the author” (Freud, 1901).(2)

Yet the work is read and attacked for those postulates, and it is for those that Gershom Scholem, who had lived near Freud in Vienna on the brink of the Nazi darkness, criticizes him, denouncing the ephemeral nature of the idyll between German and Jewish culture. (3) The reversal of the biblical legend of Moses into a no less mythological disavowed Egyptian prince had surfaced in the exegetical discussion, and had intrigued non-exegetes such as Max Weber.(4) But, as Bruno Karsenti notes, precisely this tortuousness reveals how the “political” character of the work is the dominant one: indeed that the function of the legislator’s legend explains everything – everything for Freud, everything about Freud, but also everything about Moses.(5)

Moses’ figure is neither dominated nor domitable, but shows how the vision of God constitutes the impossible object of an investigation that assumes to the full truth of the religious experience, whose power and elusiveness are restored by the sacred texts and their respective hermeneutics.(6) Harold Bloom is the one who posed the problem in the starkest terms, speaking precisely of Scholem: “Maybe so. But one has to wonder why Scholem worked, for so much of his life, under the elusive mask of the dispassionate and learned historian.(7)

Studying Moses and the different nuances of his portrayal in different religious traditions is thus another way of reversing Bloom’s dilemma: there is no other way of working than that of the dispassionate and learned historian; but this is not a mask, it is a way of being able to arrive back first, as in a theophany, to an object whose person is an expression of God’s vision.

ENDNOTES

- See Alberto Melloni, The Greatness and Misery of Interfaith Dialogue. A Historical Critique of an Unprecedented Effort, in «Journal of Interreligious Dialogue» 30 (2022), pp. 113–133.

- David Meghnagi, Il testamento spirituale di Freud: I tre saggi sull’uomo Mosè e la religione monoteista, in «Journal of Psychoanalysis and Education», 2 (2010)/5, pp. 143–162, here 144; L’altra scena della psicoanalisi. Tensioni ebraiche nell’opera di Sigmund Freud, ed. David. Meghnagi, Carocci, Roma, 1987; David Meghnagi, Il padre e la legge. Freud e l’Ebraismo, Marsilio, Venezia, 2004; Freud and Judaism, ed. David Meghnagi, Karnac Books, London, 1993.

- See Daniel Abrams, Ten Psychoanalytic Aphorisms on the Kabbalah, Cherub Press, Los Angeles, 2011 pp. 5-14.

- Weber’s 1921 formula can be found in Meghnaghi, Il testamento spirituale di Freud; see also Yosef Haim Yerushalmi, Freud on the “Historical Novel”. From the manuscript draft (1934) of Moses and Monotheism, in «International Journal of Psychoanalysis» 70 (1989), pp 375–395; and Id., Il Mosè di Freud. Giudaismo terminabile e interminabile, Torino, Einaudi, 1996.

- Bruno Karsenti, Moïse et l’idée de peuple. La vérité historique selon Freud, Cerf, Paris, 2012.

- Bruno Karsenti, Moïse et l’idée de peuple. La vérité historique selon Freud, Cerf, Paris, 2012.

- Harold Bloom, Kafka – Freud – Scholem, Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt a.M., 2005; the problem was already present in Eliane Amado Lévy-Valensi, Le Moïse de Freud (ou la référence occultée), Editions du Rocher, Paris, 1984.

The Prophet Moses in the Three Monotheistic Traditions: Challenges and Controversial Issues

Peter Madros deceased in 2019, before the publication of this article.

Moses: Unity and Diversity – Abrahamic Perspectives

This contribution will explore the extent to which Abrahamic dialogue is dependent upon unity rather than diversity and will make reference to scriptural readings as well as interpretations about Moses.…

The Vision of Moses in Early Christianity: The Case of the Transfiguration of Jesus

“In the Hebrew Bible and in its ancient Greek and Aramaic versions, the figure of Moses is presented in a multitude of perspectives. Our focus is on the supernatural visions…

The Figure of Moses in Islam: An Interpretative Hypothesis

The figure of Moses is very complex in the Islamic tradition, both in terms of the interpretation of the Qur’anic passages concerning him, as well as what is mentioned in…

M.J. Lagrange, The Pontifical Biblical Commission and the Mosaic Authenticity of the Pentateuch

In his SOUVENIRS PERSONNELS, published posthumously in 1967,1 Marie-Joseph Lagrange (1855-1938), founder of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française in Jerusalem, comments the publication in 1906 of the answers given…

The Father of All Prophets: Moses as Prophet and the Prophecy of Moses in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Traditions

Mose – מֹשֶׁה (Mosheh), Μωυσῆς or Μωσῆς (Mōysēs or Mōsēs), موسى (Mūsā) – belongs without doubt to those figures of religious history, who have experienced an incomparably broad reception far…